Post-war reconstruction

“Ten exercise books for 50 pupils”

Universal primary education was the UN Millennium Development Goal 2 (MDG2). Accessing the situation in Sierra Leone, an official of the UN Development Programme (UNDP) says that MDG2 has not been fully achieved although he appreciates major increases in gross primary and secondary enrolment. The data is limited, however, so “it is pretty difficult to give the country a clean bill,” says the expert, who does not want his name to be mentioned.

Sierra Leone has witnessed economic growth in recent years, but it is still marked by the scars of a decade of civil war, which officially ended in 2002. The education sector was destroyed, and it had not been strong even before the war. Successive post-war government agendas have prioritised the sector, and the ambition was to attain the MDG. A number of policies and legislations were passed accordingly, including the Education Act of 2004 and the Child Rights Act of 2007. Sierra Leone has about 6 million people, of whom 42 % are 14 years old and younger.

The Ebola crisis, however, was a major setback. It forced government agencies and civil-society organisations to focus on a deadly new challenge. Schools were closed for months.

In principle, primary education has become compulsory, but many children still do not go to school even in times not haunted by Ebola. According to Michael Turay of the Ministry for Education, Science and Technology, 48 % of girls and 50 % of boys were enrolled in 2011. There are no reliable statistics on how matters have developed since then. The enrolment ratios may look poor to foreigners, but one must not forget that the school system had to be rebuilt from scratch after the war.

Turay says that, in 2011, progress was considerable – and better than in regard to the other MDGs. He points out that, in 2011, about 1.2 million primary school pupils were registered, almost a third more than in the previous year. “We may not have hit the MDG, but we are happy that we are close to there as a country,” he says.

Many more children start than finish school however. According to Thomas Dickson, a newspaper editor, this is one of two “insurmountable challenges”. The other is that education is often of poor quality.

Illiteracy rate of 60 %

“Sierra Leone still has an illiteracy rate of 60 %,” says William Sao Lamin of Health Alert, a non-governmental organisation. He adds that many of those who are officially considered literate cannot read well. In his eyes, “significant efforts should have been made to improve the quality of primary education as well as address the problem of school dropout”. Ibrahim Tommy agrees. He heads the Centre for Accountability and Rule of Law, a civil-society organisation. In his view, the government and its development partners in the donor community will need increase spending on education. Moreover he wants the responsibility for elementary schools to be decentralised to local-government agencies, so they can ensure “the efficient use of resources, including the timely delivery of textbooks and materials”.

Generally speaking, civil-society organisations want the government and donor institutions to do more to make Sierra Leone achieve MDG2 as soon as possible. Some parents feel that the free primary education the government offers is not good enough. If they can afford to do so, they prefer to send their children to private schools. They pay high fees, but are sure that their children get quality education.

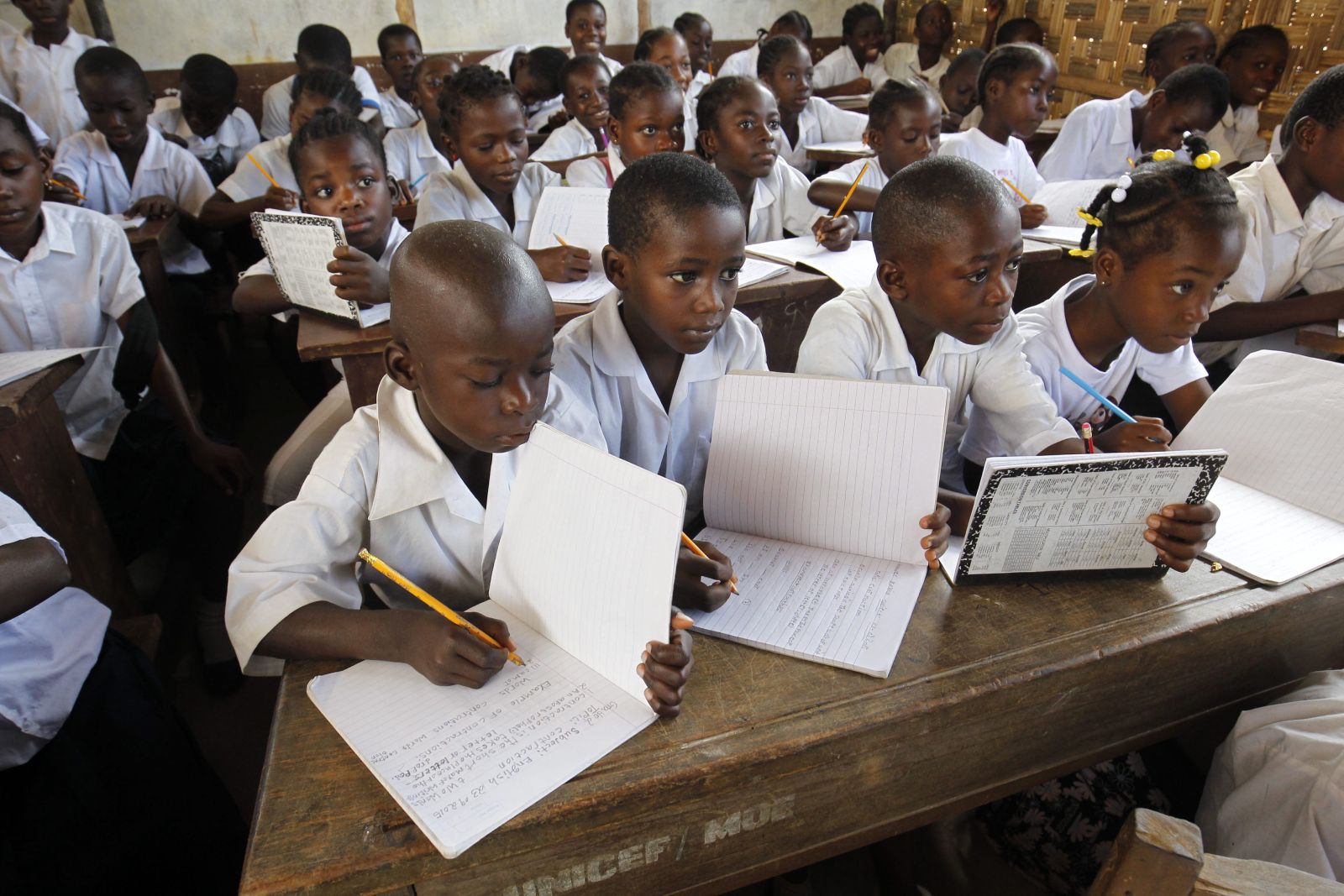

The sad truth is that school resources indeed tend to be insufficient. Abdul Bundu, who heads a primary school, says that there are not enough text and exercise books for the pupils: “We have a class of 50 pupils, but only 10 exercise books available.”

Similar issues arise in regard to accommodation. Rebecca Kanu, a teacher at a municipal primary school, complains that children do not pay proper attention because they are clustered in small class rooms without adequate seats and tables. “We have been grappling with this issue for over a decade,” she reports. The problem is that government supplies do not keep up with rising numbers of enrolled children.

Gaps are also evident in the area of teachers’ welfare. Zainab Kamara leads a team of 13 teachers at a primary school. She says that the majority of them are trained and qualified, but not all are paid by the government: “My teachers, who are not on the government payroll, are being given stipends derived from school fees.” The snag is that the fees are not paid regularly so the teachers are often not paid on time or not in full.

In principle, the government has promised free school meals. Feeding pupils would be a major incentive to stay in school, but the policy is not implemented everywhere. Kamara states plainly: “The school feeding programme is not forthcoming.”

PR officer Turay of the Ministry of Education says the World Food Program (WFP) is feeding about 267,000 school children in some parts of the South East and in the Northern Provinces of Sierra Leone, while the Catholic Relief Service (CRS) feeds about 28,000 children in the Koinadugu District. He notes that WFP does not have the capacity to feed all primary children across the country and that government will have to create the structure to ensure nationwide coverage.

According to him, $ 13 million are needed, the government would provide $ 10 million and the balance would be provided by donors. As the government officer points out, however, “school feeding is not part of the criteria of the MDG2”. Nonetheless, the government is prepared to make the effort in order to ensure that children stay in school.

As for teaching and learning materials for primary schools, he says the government has always been providing them to schools, relying on a taskforce comprising the country’s Anti Corruption Commission, the Office of National Security and the District and Municipal Councils.

“Distribution of teaching and learning materials to schools is purely based on the number of pupils registered per school year, and each pupil is entitled to a text book per each subject.” He admits, however, that the Ministry of Education is not monitoring distribution and usage.

Observers know that the capacities of Sierra Leone’s post-war institutions still tend to be over-burdened. Most of them agree that many things need to be done. Teachers’ working conditions and terms of service must improve. This includes salaries, with an emphasis on better pay for those working in rural and remote locations. On the other hand, teachers’ performance should be monitored. Moreover, incentives are needed to ensure that children, especially girls, enrol in school and do not drop out before they complete the entire curriculum.

Internationally, the MDGs have been a huge success, though not all were attained. In Sierra Leone, MDG2 has had an impact, but it has not been achieved by the deadline of 2015. The UN adopted a new set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in September, and they build on the MDGs. There is a broad consensus, however, that the MDG agenda must be completed.

Minkailu Bah, Sierra Leone’s education minister, is confident that it will be done: “Although the development climate for Sierra Leone’s primary education remains challenging in many ways, we have the opportunity of using the next 15 years to focus on what little successes we have achieved in the MDG2 and further consolidate on them.” He expresses confidence that Sierra Leone will make significant progress towards the SDGs as well.

Fidelis Adele is a journalist based in Freetown.

fid2k2@yahoo.com