Letter to the editor

The quirks of misguided decentralisation in Benin

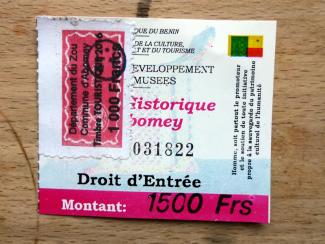

One Sunday last November, I visited Benin’s historic Royal Palaces of Abomey. The former seat of the Kingdom of Dahomey is a UNESCO world heritage site. I paid 1,500 CFA francs (about 2.25 euros) to get in, only to be asked by the man behind the counter for an additional 1,000 CFA francs. A surcharge of two-thirds on the admission price is certainly significant, and it turned out that the reason was that the mayor of Abomey had recently introduced a tourist tax.

I took a photo of the ticket, which I consider a political issue. Why do I do so? Well, a common thread running through your focus section on taxes was the negative correlation between political-administrative decentralisation and fiscal decentralisation. As occurred in Benin, central governments typically cede some rights and, more significantly, transfer some tasks to municipal authorities. However, neither the government nor the parliament want to cede the funds that must go hand in hand with the new responsibilities. Such disconnects are known everywhere, including in Germany, but they are especially blatant in sub-Saharan Africa. Lacking the funds they need, municipal authorities only rudimentarily live up to their decentralised responsibilities.

Schools fall apart, drinking-water systems are not kept up, and public spaces and buildings are neglected. The mayor of Abomey came up with a unique solution for this last challenge by the way: the moment you step out of your car to take a photo of a national monument, a city employee is likely to pop up and sell you a ticket as your contribution to “the maintenance” of the monument.

The tax dramatically cut the number of visitors to the UNESCO cultural heritage site. A museum guide told me very few locals came anymore because they too had to pay the same surcharge on the considerably cheaper ticket of 500 CFA francs. In view of plummeting numbers, the mayor reconsidered and the fee was cancelled with little fanfare in March 2018. His attempt to generate municipal funding was a clear failure, but at least it caused little lasting damage.

As a rule though, inadequate decentralisation and attempts by local authorities to recoup at least some of the shortfall cause tremendous harm. International development cooperation often contributes to making a bad situation worse. All over Benin, for example, you’ll see brand-new marketplaces, mostly built on the outskirts of a rural centre. They are easily identified due to the “funded by xyz” signs, but often some goats enjoying a bit of shade are the only signs of usage.

Such infrastructure gifts (they come in other forms too, like commercial hangars and “service areas”) are driven by the idea that local governments will charge usage fees to plug budget holes. In reality, however, they are the antithesis of development and poverty reduction. Typically, poor rural communities are charged hefty fees for services they urgently need, sometimes as simple as a spot on a market or parking at a dusty truck stop.

A market woman in Atakora, for example, may earn 1,200 CFA francs (around 1.80 euros) a day selling cassava. She’ll take home half as profit and will spend four hours walking to and from the market. Now the mayor plans to levy 300 CFA francs a day for her spot at a new market facility, cutting her income in half. It’s no wonder so many marketplaces stay empty. Some are in use, but only because there is no alternative, and, as usual, the poorest are paying the highest price.

Frank Bliss, Remagen