Urban environment

Old mirrors

Kolkata is located in the Ganges Delta. In 1690, Job Charnock established the headquarters of England’s East India Company here, and the city was the capital of British India from 1774 until the colonial power moved its offices to New Delhi in 1911. From the early 19th century on, Kolkata acquired great importance and glamour. It used to be called the British Empire’s "second city" and was centre of learning and culture as well as commerce and administration. The city played a leading role in the nation’s independence movement.

Today, Kolkata is the capital of the state of West Bengal and the third largest metropolis of India after Mumbai and Delhi. The city is densely populated with more than 24,000 persons per square kilometre and home to about 4.5 million people. Some 14 million live in the agglomeration.

It is intriguing to see Kolkata as a city of water bodies. Job Charnock set up his office by the side of a big water body called Lal Dighi (Red Tank), which still exists today. This is where the colonial government later had its offices and where the state government resides today.

Lord Wellesley, the governor general of India from 1798 to 1805, took the first initiative for planning the development of Kolkata, and in 1817 the first town development committee was formed. This committee was instrumental in the building of several major roads as well as the excavation or renovation of a number of water bodies. They served to supply water to the public.

The colonial rulers had a habit of naming the areas around a pond a "square". Typically, the squares would also include some gardens. Many of the water bodies have been filled up, but some still exist. Lal Dighi came to be known as Tank Square, and later renamed the Dalhousie Square. Of the squares with water bodies in central Kolkata, some have become centres for various activities, from swimming to political agitation. Well-known educational institutions are close to these squares which were frequented by eminent Bengali intellectuals and political leaders in the past.

A Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) road directory of 2006 lists 61 roads that were named after water bodies. Moreover, many neighbourhoods are named after a pond ("pukur") in Bengali. We have Monoharpukur, Ahiripukur, Boesepukur and many others. The sad truth, however, is that the respective water bodies have disappeared in many cases. Only their names remain.

Because of real-estate development, many water bodies in Kolkata have been filled up. Even today, real-estate promoters often use such reclaimed land for construction sites. However, a considerable number of ponds and lakes have survived.

According to the Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC), there are 3874 water bodies in the municipal area. Its list is not complete, however. I have identified more than 4500 water bodies, relying on Google’s satellite map. I was part of a team that surveyed the water bodies on behalf of the KMC at the end of the past decade. Working on projects for India’s Central Pollution Control, I have carried out a survey of the water quality as well as other environmental and social aspects of these water bodies.

My colleagues and myself found that many water bodies are quite old and have fascinating histories, preserved through oral and some written evidence. Proper documentation, however, has not really begun yet. While the KMC has taken steps to register and protect heritage buildings and places, it has not seriously considered water bodies. They are an important part of the city’s heritage and deserve more attention.

There is no official definition for a heritage water body. Our survey proposes to regard as heritage water bodies those that are:

- at least 100 years old,

- associated either with cultural and religious events, or with eminent personalities and families, or associated with history.

We started with a preliminary literature survey. At the ground level, local people helped us identify heritage water bodies. Basically there are four categories of heritage ponds:

- some predate the city,

- some are linked to religious beliefs,

- some relate to traditional events and historical families, and

- some have political and social relevance.

Faith dimensions

Hindus traditionally consider the excavation of water bodies a pious duty. For centuries, such an act of philanthropy was believed to save a rich or powerful person’s soul. Accordingly, a number of historical water bodies were excavated a long time ago. The oldest water body within the present KMC area is the Sen Digh ("Dighi" means lake in Bengali). The Sens are considered to have been the last Hindu rulers of Bengal, before Muslim invaders conquered the region in the 13th century. Many artifacts from the years 750 to 1230 have been recovered from the Sen Dighi area.

Indian religions have an organic relation with water bodies. It is a general custom that worshippers take a bath before going into the temple. Various rituals must be performed in water, so many water bodies have a religious relevance. Charak Mela is a religious festival celebrating Lord Shiva, it has been taking place by the side of Paddapukur ("Lotus Pond") for more than 200 years. Other water bodies have temples by their sides. For instance, six Shiva temples dot the banks of Chatterjee Para Pukur in southwest Kolkata. They are more than 150 years old. On the other hand, Pagla Pirer Pukur ("the pond of the eccentric Muslim saint") in southern Kolkata is named after a Sufi and is more than 350 years old.

Muraripukur locality is intricately linked to the history of India’s independence movement as the locality was the underground headquarter of armed revolutionaries. The place used to have at least eight ponds, but only one remains. A memorial to the freedom fighters was erected there by the side of the only remaining water body.

So far, we have identified 59 ponds as heritage water bodies, of which 60 % have been characterised as such for the first time. Thirty six of the heritage water bodies are more than 150 years old. Only one has an information board to inform the public of its history. About 40 % of the water bodies are of religious relevance.

Kolkata is located in a huge river delta. It is a city of water bodies and these water bodies are still the water resource for the poor. Nearly a million common people use these water bodies daily as source of water for bathing, washing clothes et cetera. Kolkata planners never bothered to consider these aspects in their water-supply schemes because the people concerned are marginalised in economic and other senses. In the past two decades, environmentalists have been fighting to protect and restore lakes and ponds both for social and ecological values.

It is time the city authorities rise to their responsibility of protecting the water bodies. The KMC needs to document them properly and survey the water quality in regard to their different uses. It needs to develop the institutional capacity to protect several thousand water bodies, prepare a management plan and implement it stringently. Otherwise the water bodies will be polluted further and subsequently filled up by the real-estate mafia. Finally, the KMC should inform citizens about this rich heritage to the benefit of future generations.

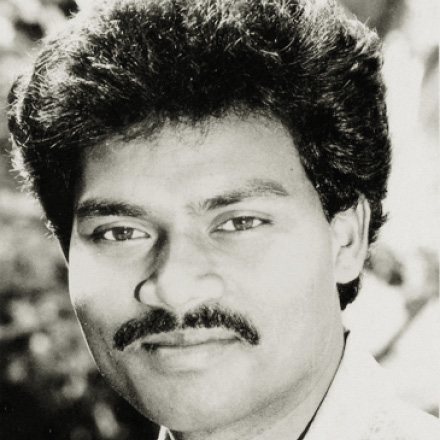

Mohit Ray is an environmental engineer and a civil-society activist. He works as a free-lance consultant. His book "Old mirrors" deals with heritage ponds and was published by the Kolkata Municipal Corporation in 2010.

mohitray@hotmail.com