Weapons of mass destruction

Nuclear obsession

North Korea became a de facto nuclear-weapon state (NWS) in 2006. It has since conducted no less than five nuclear tests. The latest was carried out in September 2017, and according to North Korean state media, it featured a thermonuclear weapon or hydrogen bomb for the first time.

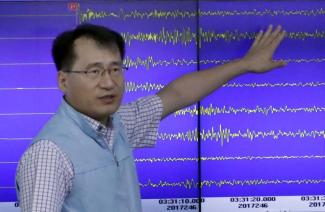

The explosion had an estimated destructive yield of 250 kilotons. It was indeed far greater than that of ordinary nuclear weapons – which usually have a yield in the range of tens of kilotons. It also generated an earthquake with an estimated seismic magnitude of 6.3.

Raising the stakes even higher, North Korea’s sixth nuclear blast came shortly after its first test of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) on 4 July. According to experts, the range of the missile was between 6,700 to 8,000 kilometres, which means it could reach targets in the mainland USA. Pyongyang tested a second ICBM on 28 July.

It is quite obvious that North Korea’s obsessive efforts over the past years to bring the US mainland within the range of its missiles are driven by fear. The dictatorship wants to prevent a US or allied attack on its territory. The consensus among international observers is that North Korea is keen on the deterrent impact of nuclear weapons and long-range missiles.

The fates of former Iraqi strongman Saddam Hussein and Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi have surely not been lost on North Korea’s leadership. Both strongmen were at loggerheads with the United States and did not hesitate to challenge international norms. Both were eliminated soon after discontinuing their nuclear programmes. They lacked a strategic deterrent.

A “rogue” state as North Korea has reason to believe that its nuclear capability can provide it with something like impunity. After all, Vladimir Putin’s Russia managed to get away with the annexation of Crimea in early 2014 thanks to its massive arsenal of nuclear weapons. According to international law, Crimea is part of Ukraine.

For North Korea, however, the nuclear programme serves other needs and purposes as well. The country is marginalised in the international community, thanks to its reclusive communist regime and an ideology that glorifies self-sufficiency. There is a notable lack of allies and friends. Pyongyang has been described as a “rogue” regime by many western powers and their Asian allies.

In this setting, the possession of powerful nukes implies membership in the elite club of nuclear weapon states, and that is apparently perceived to compensate for the identity problems emanating from isolation. North Korean leaders seem to believe that nuclear capability bestows on their state the recognition and status it otherwise lacks.

This is all the more important given that North Korea is subject to tough international sanctions which were imposed by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). The last round of UNSC sanctions against the country was passed on 11 September, restricting its crude oil imports and textile exports. UNSC Resolution 2375, which was even backed by traditionally more sympathetic states such as Russia and China, also bans North Korean nationals from working abroad.

In such a harsh international environment, nuclear weapons may play in state-society relations. The sanctions hurt North Korea’s economy and its people, but there is little doubt that the mastery of nuclear technology has stoked nationalism. Nuclear prowess serves to legitimise the despotic leadership in the absence of democratic institutions and fair distribution of national resources. It is ironic that the arms programme accomplishes these things for the regime, even though the country is paying an incredibly high price.

Maysam Behravesh is a political scientist who is preparing his PhD thesis on aspects of nuclear proliferation at the University of Lund in Sweden.

maysam.behravesh@gmail.com