Our view

Movements are often formally leaderless - and yet powerful

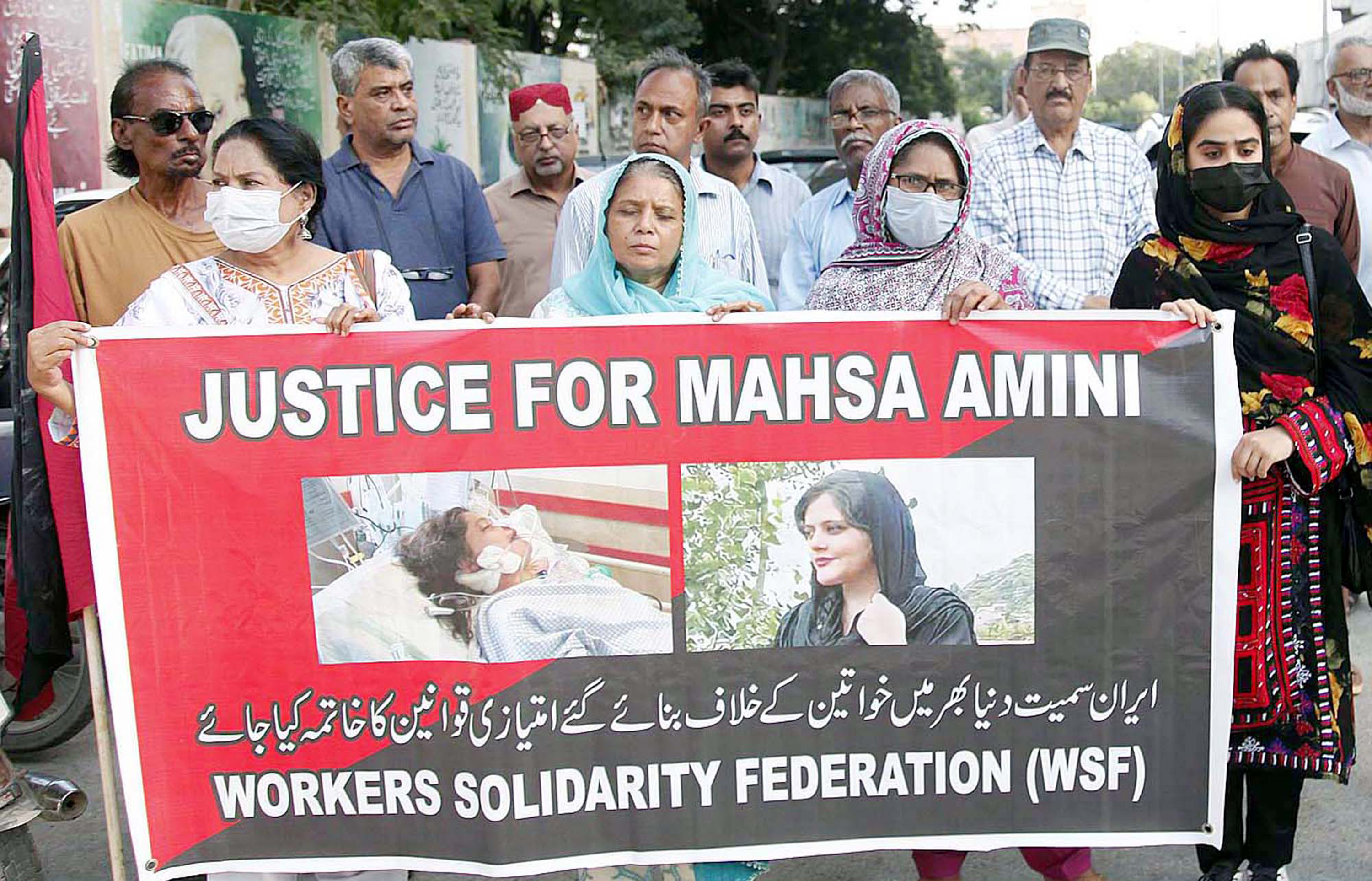

Our era is restless, marked by many political movements. This year, the Black Lives Matter movement spread from Minneapolis around the world. In 2018/2019, “Fridays for future” became the slogan of climate-aware teenagers on all continents. In 2011, the Arab Spring rocked much of North Africa and the Middle East. Recent pro-democracy protests look like an Arab Spring 2.0 in some countries, but similar movements are evident in faraway places too – including, Chile, Belarus and Thailand, for example.

Some basics deserve attention. Unlike formal organisations, political movements typically do not have a legally defined leadership. They arise from loose networks of like-minded people who share a common cause and, for one reason or another, decide that a grievance has become intolerable. Leaderlessness has several implications. The two most important are that:

- movements are hard to repress because the authorities cannot simply silence the top level, and

- movements are prone to utopian demands as no one is in charge of making dreams come true.

To achieve goals, more is needed. Accordingly, political movements tend to have close relationships with formal organisations (associations, co-operatives, parties et cetera), which they either found anew or discover to be supportive of their cause. In a democracy with secure civil rights, new movements fast become yet another facet of a highly diverse civil society. Typically they demand more inclusion, environmental protection or social justice, so they find allies accordingly. Where, however, civil-society space is restricted, political movements challenge the political order itself, so demands for democracy take centre stage. Democratic systems are actually stronger than autocratic ones because they can respond to new demands without seeing their very existence under threat.

Angry people – especially if they are young – endorse radicalism. Some, though not all, equate radicalism with violent action. They are misguided. Ample historical evidence shows that non-violent civil disobedience often achieves a lot, whereas militia-style operations regularly lead to new authoritarianism. Repressive governments, on the other hand, are quite keen on provoking violent clashes. They know that their security forces, well-trained and well-equipped, are more likely to prevail in combat-like scenarios than they themselves are to prevail in reasoned public discourse.

Not all political movements are progressive. Right-wing populism too needs to network, leveraging widespread frustration. However, this kind of nationalism tends to be more top-down, more prone to science denial and more dependent on charismatic personal leadership. If right-wing populists feel support within the security forces – as they often do – they will be more prepared to risk the escalation of violence. If they have strong financial support from special interests, they can rely on intricate media operations to spread propaganda. Small grassroots initiatives of marginalised people do not have that opportunity. Nonetheless, the discontent they express may resonate with masses of people and trigger huge popular movements.

Hans Dembowski is editor in chief of D+C Development and Cooperation / E+Z Entwicklung und Zusammenarbeit.

euz.editor@dandc.eu