Health

Cholera spreading in Zanzibar

In an effort to stop the disease, the government of Zanzibar suspended the selling of food on the streets in March. Only few kiosks and restaurants were still allowed to operate under strict hygiene conditions. “Everyone should take part in the war against cholera,” said Mahmoud Thabit Kombo, the islands’ minister of health. He appealed to people: “Keep your environment clean. Use only treated or boiled drinking water.” In the meantime, business as usual has resumed.

Public and private schools were closed in April in an effort to control the disease, but are now mostly open again. Some facilities for small children in urban areas are still closed. Hadija Juma, a local resident, maintains that it is “better to close the schools of our area, as it will prevent our children from falling sick.”

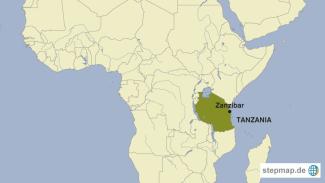

Cholera is a big problem for the small island with a population of 1.3 million people. Since September 2015, when the first case was reported, the number of infections in Zanzibar and the sister island of Pemba surpassed three thousand. In spring, an average of 20 people were being admitted to hospital daily.

Medical services are provided free of charge in Zanzibar. In spite of this, some people died in their homes. They did not get treatment fast enough.

Cholera is caused by various types of the bacteria “Vibrio cholera”. The disease is spread mostly by water and food that has been contaminated with human faeces containing the bacteria. Insufficiently cooked seafood is a common source for infection. Poor people are especially hard-hit. Risk factors include poor sanitation, unsafe drinking water as well as the ignorance of people who do not take health precautions.

Infected persons show severe symptoms like profuse watery diarrhoea, vomiting and muscles cramps. Historically, the first case of this disease to be reported in Zanzibar was in 1836. In the mid-19th century, the disease killed about one third of Zanzibar’s population.

The worst cholera epidemic to hit this Indian Ocean archipelago more recently was in December 1997, when 200 people died and 570 others were admitted to hospital.

Following the recent outbreak of cholera, awareness campaigns continue through electronic and print media of Zanzibar as well as mobile phones, reminding people to follow health instructions like “washing your hands with soap after visiting the toilet and before eating, and only using safe treated or boiled water.” That the immediate crisis is over does not mean that awareness raising should not go on.

Ali Shaaban Juma is a journalist and lives in Zanzibar, Tanzania.

rafikifumba1@hotmail.com