Official development assistance

Systemic flaws

“Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.” The ancient Chinese proverb has long been a guiding principle of international development aid. Help for self-help is constantly propagated, and sustainability is hailed as a primary objective. Officially, sights are set on lofty goals such as poverty reduction, food security, education, health care and gender equality.

But development aid is rarely an entirely altruistic business – vested donor interests matter too. Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, for example, is explicitly supposed to help establish contacts for private-sector businesses in partner countries. That endeavour may help reduce poverty but it does not necessarily do so.

Help for self-help could mean to enable developing countries to process their own agricultural and mineral resources. The fact is, however, that many industrial economies depend on those resources, with private-sector companies having a vested interest in controlling their production, trade, processing and manufacturing. Ethiopia has many resources that it exports as raw materials to industrial countries. Coffee beans, cotton and gold are just a few. It would make good economic sense to process those commodities in the country and then export products with a higher value. But that hardly ever happens.

In Ethiopia’s case, help for self-help could also mean to turn many of the country’s lakes and rivers into resources for fishery and farmland development. The country has 74 million hectares of land suitable for agriculture; irrigation could enable more of it to be used than the mere 15 million hectares farmed at present.

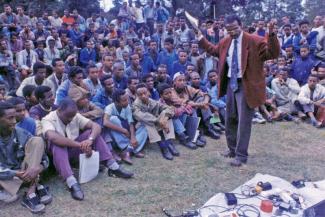

The fact that these things are not happening is not just down to donors. The successful implementation of development projects is frequently thwarted by the interests of individual actors in recipient countries. A number of years ago, for instance, an attempt to install solar-powered irrigation pumps and supply villages with electricity from solar energy failed due to resistance from Ethiopian authorities. To avoid such fiascos, Ethiopia needs to raise awareness for innovation. The good news is that the government has embraced renewable-energy technologies since the failure just mentioned.

Technology and capacity building

Infrastructure development still has a long way to go in Ethiopia: electricity, water, telephone and internet supply is poor in many places. Development is inhibited accordingly. Foreign expertise and loans may help, but local capacity-building is needed to address not just the technological but also the human causes of problems.

What would help many countries more than any form of development aid is fair and free global trade. That has long been called for, both by experts and by African heads of state like Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame. Free trade is prevented, however, by industrial country protectionism in the form of customs tariffs, subsidies and import quotas – especially for agricultural products. And agriculture is typically the most important branch of a developing country’s economy.

Instead of giving opportunities to small farmers in developing countries, the United States, Canada and the European Union export their subsidised agricultural surpluses to those countries – sometimes in guise of emergency aid – and actually squeeze local farmers out of domestic markets.

Grain from the US and EU is certainly welcomed by Ethiopia’s urban communities but it depresses prices in the markets. The same goes for milk and dairy products from the EU. Small farmers are driven out of business, and local production decreases.

If people who live in poverty and hunger are constantly supplied with food handouts, they lose their self-reliance and become dependent. Local initiative is suppressed. People stay alive, but they have no livelihood of their own. In a country that can produce adequate staple food, it is absurd to pay workers by handing out foreign food aid. Yet that is exactly what happened near Dilla in the fertile south of Ethiopia. A so-called food for work programme employed farmers in road construction and compensated them with foreign grain. That happened in an area that grows bananas, papayas, avocados, coffee and other crops.

Outflow of skilled workers

Brain drain also takes a toll. In 2014 alone, 5,718 highly trained Ethiopians were issued a Green Card for the United States. Many of them were medical doctors. While such migration of skilled labour benefits host countries, it is a painful loss for the homeland economy. Ethiopia has a serious shortage of medical staff, especially in rural areas. Its universities are severely under-staffed. To make up the shortfall, lecturers are recruited from abroad, mostly from India.

The problems outlined above are compounded by vested interests. Humanitarian and development aid are a huge international industry. It provides lots of jobs and is interested in sustaining and perpetuating itself. While individual aid workers and specific aid projects may indeed try to make themselves superfluous in the long run, that is not what major agencies do. Foreign leaders, international media and aid organisations cultivate an image of poor countries being in need or – as in the case of Ethiopia – being outright disaster zones. This overblown stereotype ensures revenue to the aid industry.

Systematic development aid would mean that developed countries accept more moderate economic growth in favour of developing countries. While there is some philanthropic commitment in the rich world, it does evidently not go this far. Another, equally important step would be for policy makers in developing countries to use aid to build efficient institutions for the future instead of chasing mainly short-term individual advantages.

Kiros Abeselom is a lecturer in agricultural economics at Dilla University.

kirosa@du.edu.et

Link:

Dilla University:

http://www.du.edu.et/