Education

Endless strikes

After several months of teachers’ strikes, the Togolese government signed an agreement with the trade unions in spring. Both the Coordination des Syndicats de l’Education du Togo (CSET) and the Synergie des Travailleurs du Togo (STT) agreed to this redefinition of teachers’ professional status. On Independence Day – 27 April 2018 – the teachers’ strike was officially declared to be over.

Atsu Atcha of CSET says the agreement makes sense, and he appreciates cooperation with the STT. However, other trade unions were not involved. The National Federation of Trade Unions of Togo (FENASYET), an umbrella organisation, did not take part.

The country has been witnessing recurrent teachers’ strikes since 2013. Some trade unionists expects more labour action in the near future. “We’ll organise further strikes if the government does not fulfil our demands fast,” warns Moustafa Abou. He is an active trade unionist and a member of both the CSET and STT. Teachers’ salaries vary from 15,000 to 50,000 CFA francs per month ($ 33 and $ 111). The minimum wage in Togo is 35,000 CFA francs ($ 64).

Meanwhile, the Federation of Trade Unions of National Education (FESEN) condemns the arbitrary detention of four teachers, all of whom belong to it. They took part in a peaceful march. “This illegal and unfair imprisonment stifles and muzzles freedom and trade union movements in Togo,” says FESEN leader Hounssime Sénon.

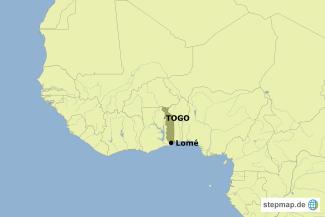

Togolese teachers want their bonuses and allowances to be fixed to the salaries of civil servants whose economic status is more secure. Teachers do not only want wages to be paid on time, but also to rise regularly. “That would help us to meet our needs,” says Massara Gbétoglo, a primary school teacher in Lomé, the capital.

“In many schools, the local community has to raise money for teachers’ salaries, buildings and resources,” complains Sègnon Gamè, a temporary teacher in Cinkassé, a remote northern village. “We have more than 100 children in one classroom, and it is very difficult to manage them,” adds Koffi Akakpo, a teacher in Lomé.

Ibrahim Ored’ola Falola is a journalist and lives in Lomé, Togo.

ibfall2007@yahoo.co.uk