Why it would make sense to pardon Lula

The situation is bizarre and shows that Brazil's democracy is in deep crisis. Lula, as he is commonly known, is still very popular. Judges have found him guilty of corruption, but the evidence is not totally convincing. Lula has appealed to the UN arguing that his case is driven by politics and infringes on his human rights.

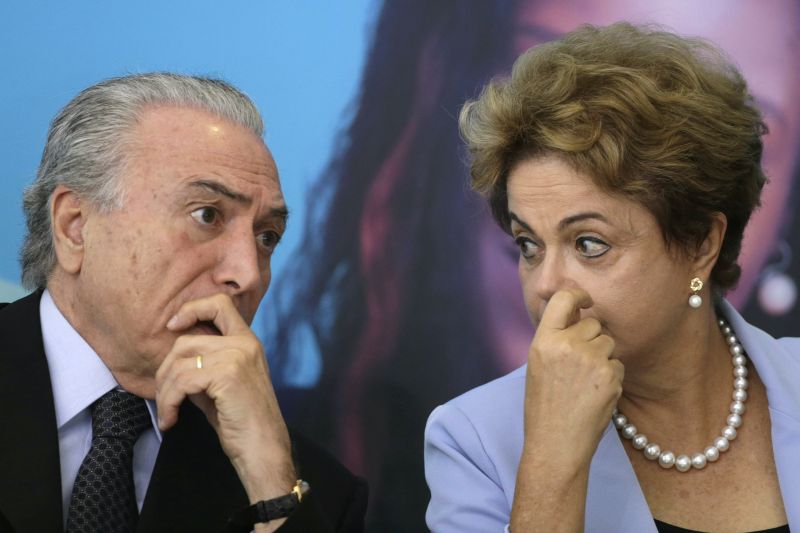

Indeed, the seaside apartment that he is said to have accepted as a bribe is considered to be worth the equivalent of a bit more than €500,000. That is a lot of money for an individual person, but only a tiny share of the huge sums linked to the “lava jato” corruption investigations in the course of which Lula was taken to court. Evidence against other political leaders, most prominently the current president Michel Temer, is stronger. The cases against them are moving ahead slower, and Temer's case has stalled entirely because legislators have decided not to start impeachment proceedings.

The irony is that Dilma Rousseff, Lula's successor and confidante, was impeached and lost power in 2016, but no case has been brought against her. Obviously, she did personally benefit from corruption. That cannot be said of Temer, who succeeded her, and many other policymakers and legislators.

Brazil's judiciary has become assertive in recent years. The investigations serve to fight corruption and end impunity. They are fundamentally healthy. The judges are right to prosecute policymakers who abuse public office for personal benefit.

Lula's conviction is a serious matter and must not be taken lightly. The problem is that it looks disproportionate to many people. Rousseff´s impeachment led to a policy reversal. Government spending and social protection were reduced radically. Lula and Rousseff had emphasised fighting poverty, but that is now anathema to Temer and the centre-right forces that support him. Under the previous centre-left administrations, Brazil had become a more united country, but society is now polarising again fast. It is true that the economy, which was in recession, has stabilised in the past two years, but social disparities are widening again. Many people have reason to feel left behind. Adding to the political difficulties, they tend to consider the coutrs to be biased against centre-left policymakers.

Lula and Rousseff never had left-wing majorities in parliament. Their administrations relied on coalitions of legislators. As long as the economy flourished, building such coalitions was not difficult. In the recession, however, former partners turned against Rousseff.

To a large extent, corruption is a systemic problem, not just a personal one. It seems likely that bribes play a role in any kind of coalition building in Brazil, whether the result is a centre-left or a centre-right majority. Judges, however, cannot prosecute a corrupt system, they can only prosecute individual people. To end impunity, they must sentence those who were proved to be guilty.

The snag, however, is that Lula looks likely to win the next presidential election if he is allowed to run. According to opinion polls, he is the clear front runner. Given that Brazil thrived under his rule and he was an extremely popular president, that is unsurprising. In spite of his prison sentence, he is the only mainstream politician who still inspires broad-based trust.

If the opinion polls are right, the person with the 2nd best chances of becoming president is Jair Bolsonaro, a right-wing radical who argues that military rule is healthy. Bolsonaro is an obvious threat to democracy. It flourished under Lula, who actually has been to prison before – as a trade union leader during military rule. Rousseff was tortured in those days. Brazil's democracy is young and Bolsonaro's apparent appeal shows that its roots are not deep.

I am no expert in Brazilian law, but I am sure there is some system to grant an amnesty. In many countries the head of state can a pardon people who were convicted of a crime, but perhaps the matter is regulated in a different way in Brazil. Whoever has the power to grant amnesties, should now pardon Lula to allow him to run for president. That he has surrendered to the police shows that he accepts the rule of law in principle, which makes an amnesty easier.

Such a pardon would have to be argued well so it does not look like the judicial decisions were irrelevant. Important points would include the systemic nature of corruption, the comparatively small sums involved in the Lula case and the nation's need for viable presidential candidates. Unless the appelate court decides that Lula is not guilty, it would struggle to make a legally coherent argument allowing him to compete in the election. These issues matter, but they should not shape judges' decision. Courts must apply the law.

Once they have done their work, however, amnesties can make sense. The reason democratic nations have amnesty procedures is that the rule of law sometimes delivers results which are unsatisfying for various reasons. Constitutions are designed to serve the common good, and if for whatever reason correct judicial procedures lead to unsatisfying results, exceptions must be possible.

In my eyes, it would make sense to pardon Lula. I don't think that will happen however. As I argued above, Brazil is deeply polarised today, and the forces that are in power now are interested in casting Lula in the role of the villain. If they want to protect democracy and boost reconciliation, however, Temer – or whoever is in charge – should pardon Lula.