Regional integration

Africa’s bewildering spaghetti bowl

Regional integration can be broadly defined as the sovereign states of a certain world region sharing policies concerning economic, social and other matters. The most prominent example internationally is the European Union. The guiding principle is that integration results in bigger markets with more opportunities and productivity-enhancing competition for all parties involved.

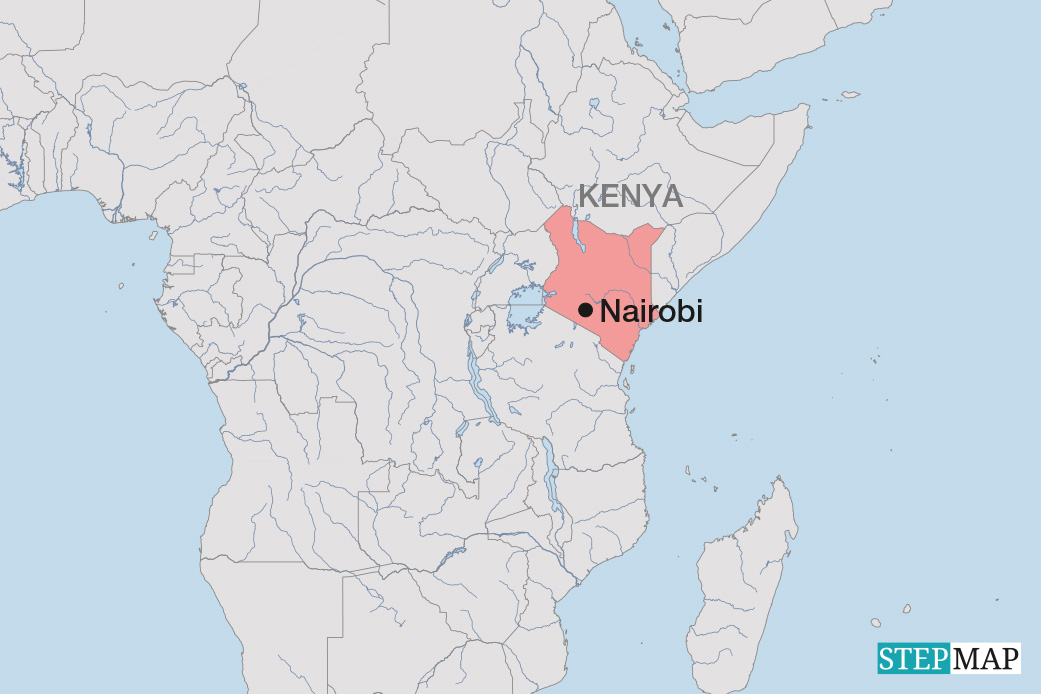

In Africa, regional integration is considered very important for several reasons. The most important one is that African nations tend to have comparatively small populations, so their domestic markets are quite small. Moreover, many countries are landlocked, which means that overseas trade is extremely expensive. Finally, they lack joint infrastructure, so each nation is basically left to fend for itself without much regional cross-border cooperation.

The process of regional integration in Africa began in the post-independence era as heads of states sought new ways to unify the continent. There are now eight RECs in Africa. However, the results have been disappointing.

Most African economies are still geared to exporting commodities and have huge informal sectors. Regional integration has yet to foster the kind of modernisation and diversification that would let African economies trade with one another and generate formal employment in various industries.

Rwanda is a rising economic star in Africa. Given that it is quite small, landlocked and not abundantly endowed with natural resources, regional integration should serve its needs well. So far, however, Rwanda’s undeniable progress results mainly from improving the domestic investment climate (see John Wesley Kabango, D+C/E+Z 2014/12, p. 454 f.) even though Rwanda is a member of the Common Market of Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the East African Community (EAC) and the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS).

As each REC has its own objectives, the multitude of overlapping RECs is a problem. A consequence is a confusing “spaghetti bowl” of different intersecting rules and regulations. In response, the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) has been launched to merge three RECs: the EAC, COMESA, to which Rwanda both belongs, plus the Southern African Development Community (SADC). It is too early to assess the impact of the TFTA on intra-regional trade flows.

Rwandan frustration

Non-compliance, however, is an even greater challenge than spaghetti-bowl entanglement of rules. According to the African Regional Integration Index, which is compiled by the African Development Bank (AfDB), Rwanda is a comparatively good performer in terms of REC rules.

In COMESA, for example, the country performs above average in terms of trade integration, free movement of people as well as financial and macro-economic integration. In ECCAS, on the other hand, Rwanda performs well in the area of productive integration and above average in trade integration. In the EAC, Rwanda is among the top four countries in areas of free movement of people and financial and macro-economic integration (AfDB 2016).

Non-compliance with rules

Other countries, however, are not playing by the jointly defined rules, so the effects of regional integration are more or less thwarted. Trade integration requires effective measures to ensure the free movement of goods, for example. Tariffs and equivalent measures that affect intra-regional trade must be eliminated, and so must non-tariff barriers. At the same time, an REC must implement common external tariffs.

It is irritating that all EAC members but Rwanda are relying on measures such as additional taxes and charges that basically have the same effect as tariffs (World Bank/East African Community Secretariat 2014). Moreover, Uganda and Tanzania are behind schedule in terms of recognising and issuing customs documents, further limiting the effectiveness of the EAC. Matters tend to be similar in the case of other African RECs.

To benefit from regional integration, Rwanda should modify its current strategy of expanding export volumes and focus more on the competitive advantages of its private sector. From 2010 to 2015, Rwanda ran a trade deficit in its interaction with other EAC countries, which tend to be more populous, rely on more natural resources and benefit from better sea links. It is no coincidence that Burundi, which resembles Rwanda in many ways, faired even worse. Unlike Rwanda, Burundi lacks competent economic governance.

The way forward

It remains to be seen whether REC membership can be made advantageous. So far, the emphasis on exports has been unprofitable since Rwanda faces high trade costs and competition from other EAC members (de Melo and Collinson, 2011). Efforts towards productive specialisation are essential in this context, and the improvement of regional infrastructure is important too.

Rwanda’s efforts to improve the skills set of its people as well as the infrastructure needed to develop the country into a hub for information and communication technology make sense. Rwandan businesses that belong to this sector are competitive and can provide services to neighbouring countries. This approach looks promising.

Moreover, ongoing regional projects such as the East African Railway master plan must be finalised to power the region’s energy and improve the business networks. At the same time, it will be useful to improve roads within the country – the better domestic transport flows, the easier it becomes to trade with neighbours after all.

Rwanda should take advantage of the new market opportunities offered by the newly formed TFTA to unlock its production potentials in agriculture as well as in industrial and services sectors, with particular attention paid to private businesses. Fully tapping the potential of the new super-REC, however, may be easier said than done.

Focussing on Tanzania, Lufuke and Kamau (2015) have assessed whether the size of an REC has an impact on trade volumes. They found out that size matters, but that small RECs actually look better because they facilitate more than trade, for instance the free movement of people. The TFTA, however, is a huge REC.

A surprising finding of Lufuke and Kamau is that, for the impacts of regional integration, it does not matter much whether a country is landlocked or not. The reason is that sea transport is not important in inner-African trade.

Alfred R. Bizoza is a director of research at the Institute of Policy Analysis and Research (IPAR) and a board member of the National Bank of Rwanda (BNR). IPAR will host this year’s annual conference of the Poverty Reduction, Equity and Growth Network (PEGNet), which links academic institutions around the world. The discussions will focus on regional integration.

a.bizoza@ipar-rwanda.org

Eugenia Kayitesi is the executive director of IPAR and a board member of the National Capacity Building Secretariat (NCBS).

e.kayitesi@ipar-rwanda.org

Kacana Sipangule is PEGNet coordinator as well as a PhD candidate in economics at the University of Göttingen and a research fellow at the Kiel Institute for World Economy.

kacana.sipangule@ifw-kiel.de

References

Africa Regional Integration Index Report 2016:

http://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Generic-Documents/ARII-Report2016_EN_web.pdf

Lufuke , E. M., and Kamau, L. M., 2015: The Impact of size of the regional economic blocs to the country’s flow of trade: evidence from COMESA, EAC and Tanzania. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology. Journal of Social, Behavioural, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering, 9 (8): 2880-2885.

MINECOFIN, 2013: Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy (EDPRS2). Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, Kigali, Rwanda.

http://www.rdb.rw/uploads/tx_sbdownloader/EDPRS_2_Main_Document.pdf

Tuffour, J-A., Balchin, N., Calabrese, L., and Mendez-Parra, M., 2016: Trade facilitation and economic transformation in Africa. The 2016 African Transformation Forum in Kigali 14-15 March 2016.

http://set.odi.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/SET-ACET-ATF-Trade-Facilitation-Paper.pdf

World Bank, 2014: East African common market score card 2014. Tracking EAC compliance in the movement of capital, services and goods. Arusha, Tanzania: World Bank and the East African Community Secretariat.

de Melo, J., and Collinson, L., 2011: Getting the best out of regional integration: some thoughts for Rwanda. International Growth Centre (IGC) Working Paper.

http://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/De-Melo-Et-Al-2011-Working-Paper.pdf