Herding

Traditional education

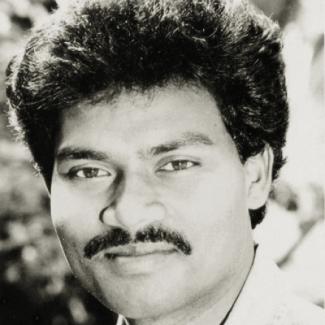

Boro Baski

Boro Baski

Today, herding is still very common in rural India. Poor, uneducated farmers own a few animals to supplement their income, and nomadic tribes tend to depend on their livestock. Nonetheless, herding is not profitable in the way that commercial livestock farming is. Moreover, less and less land may be used for pasturing. Ever more land is being farmed, illegally acquired by industries or turned into nature conservancies.

For these reasons, herding is at risk of extinction in the not so distant future. That would have a tremendous cultural impact however. In our Santal tradition, herding is the way to teach children social values and the rules of harmonious community living. In the past, all members of our community were herders at one point in their life. In many Santal villages, that is still so.

Children’s responsibilities

Poor families who have no cattle send their children to better-off families to look after their animals. As wage, the child gets a few sacks of rice, a set of clothes annually and a daily meal. This practice of child labour has continued among the Santals for centuries. It is still not considered a violation of the law that protects children from forced labour. Even the government accepts that this practice serves mutual interests.

The youngest herders are typically five to six years old. At first, the child’s responsibility is to take the goat to the field every day for grazing and ensuring it gets to drink. The child also does its best to protect goat kids from village dogs.

When they are nine or ten years old, the children join their village’s group of senior herders. The cattle are taken out to the fields at the same time in the morning. Juniors must obey the seniors. There are many other rules. More than a hundred cattle are grazed together.

Most of the herders are children and youth, but some are elderly adults. These sub-groups have different roles. The adolescents normally take the leadership in the day’s activities, which include collecting fruits and honey, catching fish, birds, crabs, snails and snakes or hunting rabbits, foxes, rats and mice. Members of the young group stay with the cattle and prevent them from eating the crop in the fields, while the elders mostly remain seated under a tree. They are available, when members of the younger generation need advice or support.

Moreover, they play the flute and sing, and they share stories and incidents with the children. In the evening before they return to their villages they roast meat and share the collected items.

A the age of 15 or so, the children slowly leave the herding group and shoulder family responsibilities at home. Boys join male members in the field work, in repairing their house, making baskets, fishing, making musical instruments or bullock carts. Adolescent girls join their mothers or elder sisters to collect firewood or vegetables from the forests and fields. When they marry, they leave their homes and start a new family.

My personal experience

In my childhood, there was no school for our village. We did not have a clock either. Our life’s rhythm was controlled by the daily movement of the sun and attuned to the seasonal cycles. The children of my generation learned a lot in our herding days, including the names of birds and animals, their songs and sounds, their timing of laying eggs or giving birth. We were taught to work as a team, and we developed a sense of democracy and gender. Moreover, we experienced friendship.

Our seniors taught us how to swim in the pond and river or how to climb on trees. We learned to play traditional flutes and stringed instruments – and how to make them from local materials. We had a happy-go-lucky life, and we were proud to carry forward the legacy of wisdom and knowledge of our ancestors through our oral tradition.

This life, however, did not last long for me. An uncle of mine convinced my family to send me to a boarding school run by Christian missionaries in a town near Kolkata. I did not want to go. I cried and struggled and even hid in the bushes for a day, but in the end, I had to leave my village. My uncle insisted that I must not come home at all so I would not “stay a Santal forever”.

When, at last, I returned home after ten years, I found myself an alien among my own people. I speak the Santal language with a strange accent. I had grown accustomed to electricity, the toilet and indoor games moreover. I had also become conscious about health and hygiene – and the relevance of clocks.

School education

In the meantime, the government has started building schools for Santal villages. Parents are increasingly expected to ensure that their children get formal education. The choice is now between continuing the carefree, traditional way of life or going to school. Because lessons are held in Bengali, which to us is a foreign language, school is quite tough for many Santal children initially. My village is privileged because, thanks to support from German donors, we are running a non-formal school that I have written about in an earlier edition of D+C/E+Z (2009/7–8, p. 280 ff.)

Many parents understand the merits of formal education. Basanti Mardi is a middle-aged Santal mother who was a herder in her early age and only went to school up to class four. Her school years were good for her. She says: “When I go to the market, I can read signs and count money, and I could get small jobs in town if I needed to.” She sent her own two children to school, and her son is actually a university student today. His mother expresses the conviction that “education is progress”.

Sundar Hembrom agrees. He is an educated Santal. He is an engineer by profession and a creative writer. He points out that Santals nowadays can hardly fulfil their basic needs from herding. However, many Santals are still very poor and, especially in remote rural areas, the youth lack educational and other opportunities (see my essay in D+C/E+Z 2013/06, p. 241 ff.). Economic development is a huge challenge for Santals. It is quite clear that herding does not do much to secure our livelihoods today and will not do so in the long run. However, we cannot be expected to get alienated from our tradition and cultural moorings. Giving up herding altogether would affect our sense of community and identity.

Boro Baski is a teacher and social worker with the community-based organisation Ghosaldanga Adibasi Seva Sangha in West Bengal. He was the first person from his village to go to college as well as the first to earn a PhD (in social work). The Adibasi Seva is supported by the German NGO Freundeskreis Ghosaldanga und Bishnubati.

borobaski@gmail.com