Rural life

Lost in translation

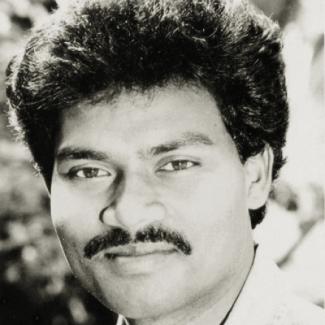

Baski

Visiting the village museum.

Baski

Visiting the village museum.

Two years ago, I contributed an interview with a renowned Santal writer, Dhirendrath Baskey, to a documentary film. We met in Bhimpur, a village where American Baptists came to work among our Adivasi tribe as early as 1860. I found it depressing that I could not find a single other elderly Santal man who could tell me about Baskey’s lifetime in our language. In Bhimpur, a place of great relevance in Santal history, the people today show no pride in our culture – and perhaps even worse, they know little about it.

This is the dark side of missionary activities. The Christian missionaries prohibited Santal culture, especially dance and music, so the tribal people who grew up in their environment got a modern education but were deprived of affinities to their own traditions and values.

Things were no different at the Mulpahari mission until the late 20th century. That is where the Norwegian missionary Paul Olaf Bodding worked. He is remembered today for documenting Santal culture (see main essay). On the other hand, Ruby Hembrom, a Santal intellectual and publisher, told me that her father was forced to leave the mission because, as a teacher, he had staged a cultural programme that included the use of Santal drums. Due to that rigid stance, a great cultural gap opened up between Christian and non-Christian Santals.

In the past few decades, however, missionaries have become more appreciative of tribal culture. Especially the Jesuit and Salesian orders of the Roman Catholic Church understand that it is important to empower tribal youth by relying on Santal traditions, including songs, dance and theatre. The Johar Human Resources Development Centre in Dumka, Jharkand, and the Santal Museum at the Don Bosco School in Azimganj, West Bengal, are doing good work.

The truth is that Bodding actually planted the seed for saving Santal heritage more than a hundred years ago. His appreciation of the Santals and their culture spread far and wide. Personally, I found it fascinating to meet two Norwegian ladies, Nora Irene Stronstad Hope and Gunvor Fjordholm Holvik, at a university event in Oslo last year. They are the descendants of missionaries and were born at Benagoria and grew up at Chandrapura Mission.

Speaking good Santali, Stronstad told me: “We still live in two different worlds.” Both women have fond memories of growing up in the Santal village with its clean mud houses in the midst of Shal trees and ample freedom of playing and roaming around with Santal kids of their age (also note essay on Santal youth).The second world is Norway, where they now live with their families. Stronstad said: “We share with them our experiences but it is hard for them to realise what we feel.” She finds news about forest depletion, environmental destruction and other hardships in India painful. We will stay in touch – and thanks to modern technology, that is not difficult.

It is encouraging that there is empathy with our fate in Norway and that a deep affinity to our culture is being felt there. This is a good start for further cooperation, and it can help to bridge the gap between Christian and non-Christian Santals. At the same time, it is depressing to know that, unlike two elderly ladies in Scandinavia, many members of our community in India are no longer able to speak our language.