Intervention

Françafrique à la Hollande

picture-alliance/abaca

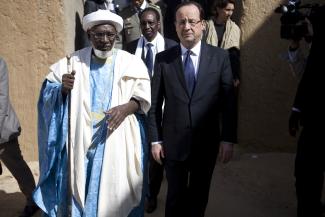

President François Hollande visiting Timbuktu in February.

picture-alliance/abaca

President François Hollande visiting Timbuktu in February.

Ever since François Hollande became president of France in 2012, he has been promising to re-define his country’s relations with its former colonies in Africa. His predecessors, from Charles de Gaule to Nicolas Sarkozy, cultivated a network of influential contacts which determined who was to be in power in which African country. Hollande wanted to end this kind of “Françafrique” and neither interfere in African affairs nor deploy troops to the continent. When Sarkozy ordered French soldiers to Côte d'Ivoire in 2011, Hollande expressed harsh criticism.

Hollande has not been in office for even a year, and the realities and complexities of Franco-African affairs have already caught up with him. The intervention in Mali proves that Paris is not forsaking the post-colonial residues of direct rule, thanks to which it has enormous influence in its former colonies.

The Malian people and the international community welcome the French intervention that succeeded in driving Islamist militias away from Gao and Timbuktu in cooperation with Mali’s army. Many Africans, however, are not comfortable with neo-colonial implications of the French army re-conquering Kidal on its own. They similarly resent the French advice to Mali’s government to negotiate with the rebels as they consider the French to be too soft on rebellious ethnic groups.

Mali’s underlying Problem, the hostility among diverse ethnic communities, has become evident once again. Most Malians oppose talks with the Tuareg rebels of the MNLA because their demands for autonomy fly in the face of the constitution. It defines Mali as one, indivisible country.

Since 1960, there have been four attempts to split Mali’s north from the south by violent means. Agreements to settle the conflict followed, but no party involved actually paid them much respect. If this area is now to become de-militarised, that will only give new scope to the illegal arms trade, provide Islamist militias with ample room for manoeuvre in the Sahara, and further weaken the national government in Bamako.

Hollande said in February that France is merely repaying a debt to Mali, since Malian troops fought on the French side in World War II. He insists he does not want to deploy troops long term. If that is so, he must leave future negotiations to Africans – to Mali’s government, to the African Union and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Such an approach would boost France’s dwindling reputation in Africa. Any other approach, however, will only put newly-won trust at risk again.

In spite of Hollande’s wishes, it is obvious that his troops cannot withdraw soon. When France launched Operation Manta in Chad in 1983, Paris promised it would last until its mission was accomplished. Three decades later, French troops are still on duty in Chad.

In the eyes of Mali’s people, the priorities now are protection from Islamist forces and hunting them down. Paris is not acting on its own in this regard, but cooperating with the African-led International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA) and the US secret services. This is the right approach, and it makes the anti-terrorism-campaign likely to succeed.

Unfortunately, however, Operation Serval may also rekindle tensions among Mali’s people. The Songhai, who live in the north just like the Tuareg and Arabs do, already feel neglected by Paris.

The political challenge is to build a democracy and a state, which so far exist in name only. Since independence, the ethnic groups have been in disagreement with one another, and Bamako must achieve reconciliation. It must also tackle the unresolved Tuareg issue. The MNLA, on the other hand, must drop its demands for autonomy. The crisis can only be resolved once all ethnic groups cooperate. Unless there is national unity, the problems will simply go on.

It is not a promising sign that, in such a difficult scenario, the EU’s first hunch was to offer military training. The one thing that, thanks to the USA and France, has really not been lacking in Mali at all in recent years is military training.

Yahouza Sadissou Madobi works for Deutsche Welle’s Africa service in Bonn.

Yahouza.sadissou@dw.de