Infrastructure

Not for everyone

ADB

The Asian Development Bank's Social Protection Index

ADB

The Asian Development Bank's Social Protection Index

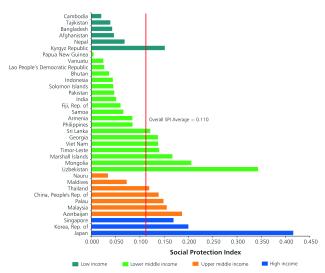

India ranks below Nepal and East Timor in the Asian Development Bank's Social Protection Index (SPI). The lack of effective measures to cushion people from risks of old age, sickness, disability, unemployment et cetera is serious concern with significant implications. After all, over 37 % of the people are officially estimated to be poor.

Formal employment in the public and private sectors goes along with contributory and non-contributory social protection programmes. However, although both sectors are large in absolute numbers, the majority of Indians do not benefit from the tax-financed and contributory schemes that come with secure jobs because about 92 % of the labour force works in the informal sector. The people concerned earn lower wages and remain uncovered by basic social protection, including sick leave, insurance against disability or old-age pensions. Unless their families take care of them, they are helpless in case of need. Women are over-represented in the informal sector and consequently remain disproportionately excluded from benefits.

In view of the need to improve matters, many developing countries, including India, have taken steps to expand social protection to people outside formal employment. Measures of this kind normally neither rely on contributions from the target groups, nor do they provide the kind of comprehensive protection that employees in the formal sector enjoy. But even though these programmes do not cover all needs, they are considered significant because they provide some security and can boost recipients' self-esteem.

In India, the National Social Assistance Programmes (NSAP) are run by the Ministry of Rural Development. They provide several kinds of assistance, including very modest pensions for the aged and widows, support for persons with disabilities and a one-time assistance to families when the breadwinner dies. Moreover, food grains are supplied to some senior citizens who do not get pensions.

Flawed programmes

The schemes look good on paper, but tend to be ineffective in reality. They all come with several conditions that are hard to meet. For instance, they are meant for those who are officially listed as living “below the poverty line” (BPL). These lists, however, are known to be politically manipulated. According to one study, 40% of the BPL cards are possessed by persons who are not poor, but take advantage of the benefits. All too often, the poor, who are normally not well-connected politically, find themselves left out. According to India's Planning Commission, less than 40 % of those that are supposed to be entitled to benefits by law actually have a BPL card, the document they need to get access to benefits.

India's official statistics tend to under-estimate poverty, so the country's social-protection policies are under-developed and under-funded. According to official data, for instance, three percent of Indians have a disability, whereas the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that about 15 % of any population is normally affected internationally. According to the NSAP administration, at least 6 million people who are accounted for as entitled to benefits remain unserved. Activists argue that the numbers of uncovered people must be much higher. It makes matters worse that someone has to have a severe form of disability and be older than 18 years to be eligible for a disability pension. Many people concerned simply do not live long enough to ever claim benefits.

Even more poor people, however, never even try to seek medical or social support at all. The procedure for accessing the benefits is often complex. A World Bank study revealed, for instance, that more than 70 % of those with disabilities could not get government support because they could not handle the bureaucratic processes. Applicants need several documents and must visit government offices several times, which is expensive particularly if the person concerned lives in a village. The paper work and the logistics of claiming benefits all too often serve as a barrier that keeps needy people away.

India's social-protection programmes, moreover, tend to be stingy. The central government pays less than three euros worth of NSPA pension per person and month. In some cases, state governments top up those pensions to a maximum of € 12. These sums are obviously not enough to meet the most basic of needs, but they may be the difference between survival and starvation.

In spite of all these challenges, social-protection programmes are becoming ever more important because of demographic change. Most of India's elderly persons are not covered by any pension scheme. They continue to work for as long as they can and depend on family support. Family life is changing, however, with the nuclear family becoming more prominent. The support that extended families provided in the past cannot be taken for granted any more. It is evident that, in the future, more aged persons will be vulnerable to risks.

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) is considered to be a major achievement in the fight against poverty. In recent years, it was the most significant social-protection initiative in India. MGNREGA was launched with the objective of enhancing the livelihood security of rural people. It guarantees 100 days of minimum-wage employment per year to one adult person per household. The programme now accounts for 38 % of all non-contribution social-protection spending in India. It has made a difference and helped the governing coalition, which is led by the Congress party, to win the general elections in 2009.

From a social-protection perspective, however, it is important to recognise that some of the most vulnerable groups cannot be a part of public-works programmes like MGNREGA because these programmes demand physical labour. The aged cannot take part, nor can persons with disabilities. MGNREGA is important, but it is not enough. Social protection, after all, must reach the most impoverished and vulnerable people – and not only the able-bodied. Those who are most in need tend to be the least vocal and visible.

Conclusion

Social protection programmes matter to both the poor and the non-poor. In India, the privileged section of society enjoys formal employment and is cushioned from the uncertainties of life. The vast majority, however, is unprotected. In spite of impressive economic growth, India is still among the nations that spend the smallest shares of the GDP on social sectors, including health and education, which are decisive for development. Social protection, however, is not charity. It is important to recognise that it is a state responsibility towards the citizens. The Indian state must do more to serve its people well.

Ipsita Sapra is a sociologist at the Hyderabad campus of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences. Her PhD thesis dealt with young people with disabilities.